March 8, 2021

As many schools and universities continue some form of remote learning and virtual instruction in 2021, the ICAA would like to provide a forum for faculty, researchers, and students to reflect on the role of digital resources in their research, lesson planning, or exploratory learning. In this post, we feature two accounts from recent graduates from Rice University and former ICAA interns (summer 2019), Grace Earick and Ellie Mix, written in the summer of 2020. Ellie Mix shares her experience finishing the fall 2020 semester at a remove from the library, while Grace Earick forges connections between her research interests and familiar surroundings after relocating to her hometown. If you are interested in contributing to Papelitos blog, contact ICAA Research Specialist Liz Donato at edonato@mfah.org.

New Ways of Working: Writing a Paper During a Global Pandemic?

Ellie Mix

When my university closed down in March due to the spread of COVID-19, the library was no longer a place I could go to get lost. Although attending lectures about Latin American artists Wilfredo Lam and Xul Solar over video chat was very manageable, conducting art historical research during a global pandemic proved more challenging. Unable to browse the shelves for books, I turned to Google’s search bar to learn more about Tarsila do Amaral, a leading figure of Brazilian modernism. After a quick tour of the top results, it became apparent that the sources I needed to write my final paper were few and far between—most of the print matter on Tarsila’s life and work had either not been digitized or placed behind a paywall. One too many messages reading, “Pages 2-12 are not available in this preview,” sent me spiraling.

Sooner or later, I made my way over to the MFAH’s online Latin American and Latinx art archive at the International Center for the Arts of the Americas. Despite being a former curatorial intern at the ICAA, I was just now starting to fully appreciate the power this resource holds. While conducting my analysis of the racial politics in Tarsila’s early oeuvre, I found that the ability to access primary sources was crucial to my success. Reading and visually analyzing the digital surrogate of the 1928 Manifesto antropofago, I learned about the foundational role the artist played in constructing an anti-colonial—yet still deeply fraught—visual national identity for Brazil. Together with her husband Oswald de Andrade and her friend Raul Bopp, Tarsila encouraged local artists to create work that cannibalized dominant European aesthetic influences. As I continued to dig deeper, it quickly became clear that the paintings she produced during the 1920s came to represent the rise of “Brasilidade” itself; in a 1927 newspaper article, art critics praise her paintings A Negra (1923)and Abaporu (1928) for visually expressing a national conception of Brazilian identity.

Though Tarsila’s bright colors and voluminous forms have since gained international acclaim, examining texts that were contemporary to that time period allowed me to approach the artist’s context with a more critical eye. Documents like the 1939 Pintura Pau-Brasil e anthropofagia talk about the importance of travel in Tarsila’s life—though I was just starting to learn Portuguese, I was able to get the general gist of the text with the help of the handy synopses and annotations written by some of the top researchers in the field that accompany every primary source. Despite the language barrier, I soon discovered that the artist’s affluent background afforded her the opportunity to spend a year in Paris conducting studio visits with “primitivists” like Pablo Picasso and Constantin Brancusi, whose work took inspiration from African art. Upon returning home to São Paulo in 1920, Tarsila embarked on a grand tour of her country’s interior and took a special interest in representing Brazil’s indigenous Tupi people. In retrospect, my research not only helped me understand the specific circumstances under which key pieces in Tarsila’s canon were created, but it also generated broader questions about the power dynamics of cultural exchange in the so-called periphery as it pertains to issues of race and class.

Six months into the global pandemic, I am adapting to the new normal by making space each week to explore the depths of digital databases. For now, the production of knowledge looks a little different for scholars across the globe; as the quest for a COVID-19 vaccine continues, open access to scientific data has become increasingly important. With so many print materials locked behind closed doors, I can only hope that humanities research follows suit. For years, libraries have engaged in case-by-case digitization efforts for the purposes of preservation or preview. As these kinds of initiatives continue to gain momentum, I can imagine a world in which websites serve as the primary access point for special collections. Though funding and copyright issues will need to be addressed, I am keeping my fingers crossed that we will continue to move towards models that, like the ICAA Documents Project website, prioritize widespread accessibility at no cost to the user. Students of all education levels have so much to learn from the ICAA; while we are all still stuck at home, take a second to check out the archive’s thought-provoking papelitos on the life and work of Tarsila do Amaral.

Left: Oswald de Andrade. “Manifesto antopofago.” (Record ID#: 771303); Revista de Antropofagia (São Paulo, Brasil), no.1 (May 1928): 3,7.

Middle: Mário de Andrade. “Tarsila.” (Record ID#: 781921); Diário Nacional (São Paulo, Brasil), December 21, 1927.

Right: Tarsila do Amaral. Pintura Pau-Brasil e antropofagia. (Record ID#: 784978); RASM: Revista Anual do Salão de Maio, São Paulo, n.1, 1939. Não paginada.

“We Offer You Colors We Make” – Exploring Chicanx Murals in Albuquerque, New Mexico

Grace Earick

Driving around the older neighborhoods in my hometown of Albuquerque, New Mexico, I’m greeted by a myriad of murals nestled between adobe houses. “SOMOS UNIDOS,” one shouts in bright, yellow text that is superimposed over a black-and-white collage showing the bustle of fans and players during a soccer game. The mural is an homage to the city’s soccer team, Albuquerque United. On another is the outline of the Virgin of Guadalupe with an ear of multicolored corn in place of the Virgen herself, an homage to the sacred importance of maíz as a staple of the Indigenous diet. These splashes of color on the streets harken the legacy of the Mexican Muralists, offering an insight into the city’s ongoing Chicanx legacy within the state’s larger and multifaceted Latinidad.

The Chicano Movement (El Movimiento) arose in the mid-to-late 1960s, building momentum from the work of activists within the parallel Black Power Movement, to address the disparate economic, educational, socio-political conditions of Mexican-Americans living in the United States. Eliminating the term Mexican-American in favor of Chican@/Xican@, a contraction of “Mexicano,” Chicanismo actively distanced itself from the racism of the Anglo-American lens to define their identity on its own terms. From the Chicano Movement arose “an emerging third culture” that forged an ideology and aesthetic rooted in the barrios of the Southwest United States that blended Mexican and Anglo-American cultural influences, as explained by painter Art Hernández in his brief 1975 essay titled “Chicano Art.”

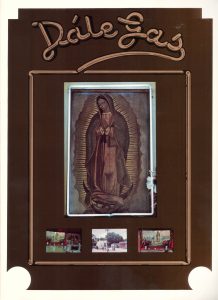

In the introduction catalog to the 1977 exhibition, Dále Gas: Chicano Art of Texas at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, curator Santos Martinez, Jr. identifies three “basic modes” or functions of Chicanx art: as a form of protest, historical awareness with a focus on Latin American and Mexican revolutionaries as a source of pride, and the push for cultural autonomy. The fervent social and political ideology behind Chicanx art led to what Sanchez refers to as the “Chicano Renaissance: A reawakening within the Barrios: a searching for an identity through the reexamination of those past events which have involved the Chicano and created the present existing problems,” which he argued were potently articulated through publicly available and/or readily distributable arts projects.

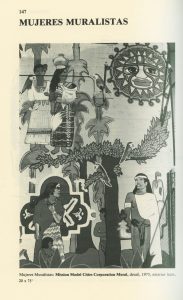

Las Mujeres Muralistas, an artist collective composed of Graciela Carrillo, Consuelo Mendez, Irene Perez, and Patricia Rodriguez, write of this power of public service and collectivity in their 1986 manifesto, “Mujeres Muralistas.” “We are women who are working together,” they open their text, distancing themselves from the individualism of the capitalist art world and the machismo that is largely associated with the Mexican Muralist Movement thanks to “Los Tres Grandes”: David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco. Emphasizing community ownership, they state, “The walls belong to no one…Our interest as artists is to put the art close to where it needs to be. Close to the children, close to the old people who often wander the streets alone, close to everyone who has to walk or ride the bus…We feel it is important that the atmosphere of the world be surrounded with life: we offer you colors we make.”

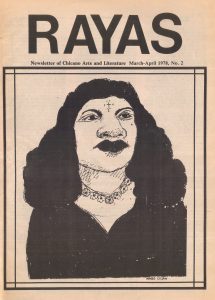

I was reflecting on how the Chicano Renaissance, collectivity, and community each manifest in the colorful walls I see in Albuquerque when I stumbled across the text, “El Mural Chicano en Nuevo México” written by Francisco Lefebre, himself a New Mexican-based muralist. Lefebre echoes many of the sentiments offered by Las Mujeres Muralistas, writing, “La importancia del mural es que la gente tiene que tener algo con qué identificarse. La expresión de la cultura de la gente es muy importante…Mi trabajo es para la gente, no para reyes o arzobispos, por eso dibujo en paredes donde todos pueden [sic?] ver.” Amid discussions of various artist collectives, barrios, and his own artistic practice, I was surprised to learn I was already very familiar with one of Lefebre’s murals: the one adorning the walls of my own high school. Situated in my school’s atrium near the building’s main entrance, Lefebre’s mural, Nuestra Juventud, collages elements of New Mexican heritage with images ranging from Pre-Columbian, Indigenous sovereignty to the resistance movements of the 20th century to position Chicanx and Latinx legacies within a global context.

I had completely forgotten about this mural before coming across this text in the ICAA archives, as it had blended into the background of my daily, adolescent life. Yet being reminded of it today as a young adult, I am confronted more critically with the importance and beauty of having a mural dedicated to and celebrating Latinidad within a school where nearly 80% of the student body identifies as Latinx, a message affirming Latinidad in the face of ongoing oppressions. Making for more colorful drives and more colorful hallways, Las Mujeres Muralistas remind us that these colors are public offerings, para la gente y por la gente.

Left:

Las Mujeres Muralistas, “Mujeres Muralistas (A Manifesto).” (Record ID# 809311); Image plate appears alongside the manifesto text, 1986.

Middle:

Santos Martinez, “Dále Gas: Chicano art of Texas.” (Record ID# 849251); The cover of the curatorial statement for the exhibition at the CAMH, 1977.

Right:

Francisco Lefebre, “El mural chicano en Nuevo México.” (Record ID# 1082170); The cover of the issue of RAYAS that this text appears in, 1978.

No hay comentarios todavía